Saturday, December 3, 2011

East Side, West Side (1949)

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Annie Oakley (1935)

Friday, October 28, 2011

Pre-Code Blues

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Fury (1936)

Monday, August 1, 2011

On Charles Chaplin

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Film Noir List as of 6-19-11

So it's come to this; I'm making lists. I kind of dislike the idea, but it allows me to catalogue what I like most about the style that is film noir (or whatever else I plan on listing). It's nothing more than a way to organize my thoughts. I'll update this list whenever I see fit, and there are actually about 30 more on my complete list that I haven't gotten to putting here.

I was fairly generous in defining film noir, to the extent that I don't consider it a genre. Hence, you will see Victorian-era Hangover Square rank higher than seedy crime drama-ish Double Indemnity. I generally adhere to the 1941-1959 era, however there are exceptions. No way am I an "expert," nor do I really want to be one. This list is merely a tool for organization.

I view film noir more as a stylistic choice than a genre, so what I look for are those movies that work on an emotional, visceral level. Summarizing in a single sentence what I like about film noir is a futile exercise, but I generally gravitate towards movies where characters we like are thrown into a bad situation. Anything that reflects the post-WWII milieu—often through the eyes of a veteran—is welcome, so long as it retains that emotional pull.

Since emotion is my guide, I find myself favoring something like Leave Her to Heaven over Murder, My Sweet. I really don't feel like detectives, blackmail, bribery, adultery, or whatever might be regarded as characteristic of film noir is really what makes the style worth watching. For me, these things are merely framing devices; what a movie is "about" is irrelevant; what matters the most to me is how well a movie is able to make me feel for its characters and absorb me in its atmosphere.

Here we go!

Night and the City:

Undiluted noir at its very finest, it’s a marvel to watch. Here, Richard Widmark manages to achieve a rare balance of sleaze and charm that only he can do. Jules Dassin’s heroes are often so ambitious, in an almost admirable sort of way, with the romantic notion that they can make it by their own rules. Yet their defiant spirit is their undoing, both spiritually and pragmatically. Harry Fabian cheats those who care for him and is willing to use any means to get ahead, with a nonchalant disregard for who he might hurt. The world of realism he chose to defy strips him of his Icarusian wings. The ending is perfect, in a sympathy-for-the-devil sort of way that humanizes the slimeball in his desperate, last-ditch bid for repentence.

In a Lonely Place:

My second favorite Bogart performance, but easily his most complex. Nevermind the whodunit angle, which doesn’t seem much of a concern. If anything, the murder seems more like a pretext to explore Dixon’s surprisingly violent tendencies. The focus of the picture—and its great strength, I think—lies in seeing Bogart’s propensities for violence as a constant undercurrent that threaten to undo the happiness he finds with Laurel. Her placating influence isn’t enough to override her fears of the man she loves. This dichotomy of fear and love charge the picture with uncertainty—an element that is undeniably noir.

Ace in the Hole:

Wilder takes aim at, well, pretty much everyone. I can’t think of another movie that better implicates the general public with a sadistic urge so openly and directly. Sure, Hitchcock did it in Psycho, but he was subversive by comparison. Ace in the Hole isn’t exactly subtle, taking the public’s recreational obsession with one man’s misery and comparing it to cannabilism. Mountain of the Seven Vultures? Yes, that does have a ring to it.

Out of the Past:

I really wish Jane Greer had more starring roles. For me, there has never been a more complete example of what a femme fatale does. The archetype is too often simplified as an unbelievably beautiful, yet dangerous, woman men fall for. What makes Jane Greer’s Moffat special is her incredible likeability. Seeing her walk on the beach “like school’s out” gives her an air of innocence that’s very endearing.

Leave Her to Heaven:

Proof that film noir is neither a genre nor a silly checklist of ingredients. Like a noose, the fear and uncertainty that inform Leave Her to Heaven tighten slowly but surely. Without any straight villain to point the finger at, the picture has an oddly disatisfying conclusion. Blaming it on insanity provides a cold comfort, I suppose, but the fact remains that these horrible crimes were commited by a woman with no malcontent; she did them out of some misguided notion of love. What makes this movie such an unsettling experience that firmly cements it in the world of noir is this brilliant juxtaposition of serene beauty with the cold, almost mechanical progression of violence.

Laura:

The infatuation with an image. Laura’s a movie with a curious version of the femme fatale archetype, forcing us to broaden our vision of what the term even means. Without Laura, there would of course be no murder, but it’s as if she as a person isn’t the cause, but rather her image that serves as a catalyst.

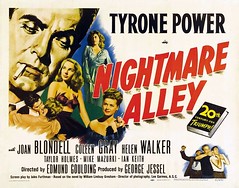

Nightmare Alley:

In some ways, a spiritual sibling of Night and the City. Both have an ambitious young man willing to do anything to climb his way to the top. Harry and Stanton eventually find themselves losing to even bigger and more vicious crooks than themselves. Yet, I’d be cautious in drawing too many comparisons because they are ultimately different movies. Nightmare Alley’s brilliance lies drawing a very likeable portrait of the carnival troupe as a sort of family and contrasting this with the unintended consequences of Stanton’s selfish ambitions.

Fallen Angel:

Linda Darnell is one of the most photogenic of Hollywood’s classic era, and combined with Preminger’s crisp photography, Fallen Angel is one of the prettiest noirs to look at. Beautiful contrast, both visually and thematically, helps create an alluring atmosphere filled with all of noir’s usual suspects. Two things people kill for—sex and money—are manifested separately into the fiery-yet-poor waitress and the bland-but-wealthy heiress. Darnell seems to be killed off a lot in her movies, but considering how bright and ferocious her screen presence is, maybe it’s understandable. Dana Andrews is a favorite; I really appreciate that calm façade he projects because it allows him to be quite versatile in what emotions he hides beneath the surface.

They Drive by Night:

Arguably not a full-fledged noir, but I’m willing to accept it as such, considering how ridiculously good Lupino is. Her Lana, married to a rich, older man while physically repulsed by him seems a blueprint for the femme fatales to come. The woman driven by self-preservation is a staple of film noir, perhaps reflecting a changing attitude in America at the time. They Drive by Night seems ahead of its time in this regard.

Side Street:

Very much like Mann’s Desperate in how it achieves its noir vibe. Farley Granger is so relatable; he’s a regular Joe just trying to make things better for his family. Tempted by an easy score, he’s pulled into the seedy crimeworld. This almost sounds like Hitchcock, but it isn’t. It lacks the exhilaration and humor of the big guy, instead focusing sympathetically on an everyman’s plight. What I like about the noir style is how readily it implants the seed of guilt into a person; Granger’s likeability comes from how believable his intentions are.

Sunset Blvd.:

Utterly unique as a noir, but with an atmosphere that reeks of the style. I’ve grown to be very sympathetic towards Norma; she’s kind of like a puppy dog. Joe’s less likeable, but his motivation is understandable. He’s like her personal gigolo, exchanging his company for materialism and security. Like so many film noir, there isn’t really a single malevolent person. If we’re to point the finger anywhere, I suppose it’s the Hollywood milieu itself, in which self-gain comes before anything else.

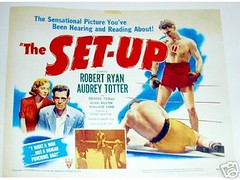

The Set-Up:

Like Sunset Blvd. the aging celebrity is thrown to the wolves; Stoker’s reached his expiration date, so his sleazy manager tries to squeeze whatever dough he can out of the waning boxer. Yet Stoker has an almost Dassinian quality to him—a defiant spirit that is eventually crushed by those he opposes. Male castration has perhaps never been captured in such a swift, brutal, and elegant manner.

On Dangerous Ground:

It’s been some while since I’ve seen this, but the score remains crisp and merciless in my mind after all these years. The anger coursing through Ryan is arguably the best rendition of a noir-cop. This movie, like In a Lonely Place, has a striking contrast between violence and tenderness that create both a fear of, and for, the protagonist.

Force of Evil:

John Garfield’s amazing here, but I love the pride that his brother has as a small-time crook. Sure, they’re both thieves but there’s something admirable about Leo’s unwillingness to sell his soul completely.

The Postman Always Rings Twice:

I like this more than its heavy-hitting older sibling Double Indemnity. I think the kind of noir I like the most is one that inspires a degree of sympathy (or at least empathy) with even the worst of scoundrels, and I find Wilder’s movie entertaining, but his characters too coolly stylized. I think John Garfield and Lana Turner’s characters feel more human because their actions don’t feel as polished; they make mistakes and they panic; they don’t feel like professionals, nor do I think they should. The older man/younger woman dyad also feels better developed which, for me, is always a plus.

The Third Man:

In many ways, a slap in the face to the wide-eyed Romantic American. Probably the most successful noir to fuse post-War realism with expressionist drama. I generally find those documentary-style police procedural noirs rather dry. The Third Man brilliantly manages to capture that realistic feel while dramatizing its ideas, rather than simply telling us. Visually, there is perhaps no other noir that surpasses it.

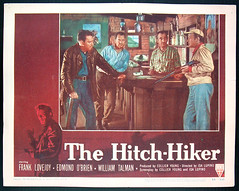

The Hitch-hiker:

Fear. Tension. Helplessness. The threats to our innocence; it’s all there. This is actually the only Lupino directed movie I’ve seen but I love it. This is a lean movie lacking the convolutions we normally see, but stylistically, it works. I’m partial to those noirs that emphasizes a couple of regular Joes falling out of their comfortable lives because I think it says a lot about the style. Try not to cringe during the William Tell scene.

Pickup on South Street:

This has a rather unglamorous style to it that, like its characters, retains a likability and humanity. It’s a lot of little touches, like Widmark’s dinky little rivershack or that he cools his beers in the Drink or Jean Peters’ raspy voice or that her name is Candy. There’s a very worldly feel to these characters; they know they don’t lead the most honorable of lives, but they have a certain pride that ennobles them.

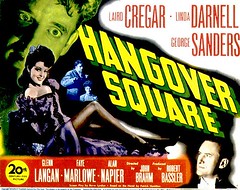

Hangover Square:

Not noir as we usually see it, but I think the fear of violence lurking within the benign is very, very well done. This is one that’s probably best to simply see, partly because I wouldn’t want to anger the spoiler-police.

Kiss of Death:

Mature is very likable here because in spite of his actions, his motivation is very relatable; all he wants to do is have a safe life for his family. It’s not something I feel needs to be expounded upon because it works on a very emotional level, even for film noir.

Dark Passage:

I’m actually not too sure what to say, but it’s very, very entertaining, to say the least. I suppose the fascination lies in seeing how much Bacall trusts a man she doesn’t even know. Again, it’s that sympathy-for-the-[apparent]-devil.

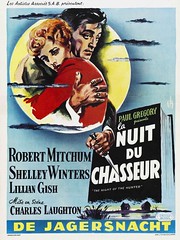

Night of the Hunter:

Unusually morbid for its time, I guess it’s no surprise Laughton didn’t survive as a Hollywood director. One of those movies that has entered filmic iconography, to the point that scenes are instantly recognizable even if you haven’t seen it before. Mitchum’s creep factor is off the charts; he’s relentless in this picture—the very essence of a threat to innocence.

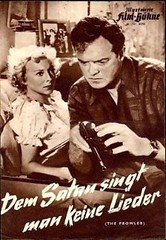

The Prowler:

I really need to see more Van Heflin movies, but between this and Act of Violence, the man definitely deserves a place as one of noir’s finest actors. The brilliance of the movie is in not having a villainous character, only villainous tendencies lurking within. Heflin’s actions are amoral, but a part of me still roots for him with Evelyn Keyes over her nearly nonexistant husband. Like Postman, here’s another instance of a tryst between a young, virile man and a woman behind the back of her wealthy, yet physically lacking, old husband.

Private Hell 36:

Odd placing this behind The Prowler, since both have cops thinking they can get away with anything. Ida Lupino, if not my favorite actress, probably stands as one of Hollywood’s most versatile; she always gives it her all, no matter how bad the movie is, it seems. This story feels surprisingly modern and it never feels like its dragging its weight; everything shown has significance, thematically.

The Big Sleep:

You know, I really don’t feel like commenting on these Bogie-Bacall noirs is necessary. They’re just really good.

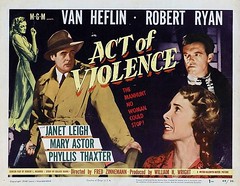

Act of Violence:

Absolutely brilliant, and maybe it deserves to be higher. Guilt is a staple of film noir, and and instilling it into a WWII vet like Heflin’s character reminds us of the heavy influence the war had on Hollywood stylistically. While this might make these movies seem more like “message” pictures (and some of them are), it speaks more broadly to the way the medium itself reflects the society that created it.

Scarlet Street:

Edward G. Robinson wearing a flowery apron... 'nuff said? Probably not, but this is probably my favorite Fritz Lang movie. With the possible exception of M, we probably haven't held such sympathy for a murderer.